Here are some questions and thoughts I have about the whole issue of "sustainability". (I am sitting on a plane and thinking out loud to myself about this issue of "sustainability").

First, I always try to ask myself -- exactly what is the question that is being asked here, and, equally important, where is that question coming from? What is the motivation for the question? And what are the assumptions that underlie the question?

And this question, like many other questions that project leaders and evaluators encounter, reflects the not unreasonable concerns of the Funding Agency. In this case, I think the question might be expanded from the funder's point of view as follows:

The funder (in this case, NSF) : "We have invested millions of dollars in your district, This has been money aimed at building your capacity, at doing the initial training needed and at supporting the very large effort that is needed to accomplish a district-wide curriculum implementation effort. So we want to know how if and how the district is now taking on the task of "sustaining" the program that we have invested heavily in so that it can be put in place."

The theory of the (LSC) grant is that by the end of five years the program will be "fully" implemented, that is, all teachers will be teaching the designated curriculum. Furthermore there is an assumption that that an infrastructure will have been put in place to support the ongoing needs of the program. That is, (for elementary science) science kits will be purchased, a materials warehouse set up; teacher leaders set up to conduct workshops; and assessments designed and put in place. All of this results in a fully functioning program that is centered around the high quality usage of a well designed curriculum...And so, not unreasonably, the funder wants to make sure that the foundation they have paid to put in place, and the house that has been constructed with their money , will both be maintained.

So in one sense sustainability comes up as a question because the funding agency wants to make sure that its investment is not lost.

From the point of view of the district the question of sustainability might look a little different:

The district: From their point of view the situation usually is that they have deeply enjoyed and appreciated the benefits of having the NSF grant. They have appreciated the work that the TOSAs, and teacher leaders have done. Usually they are very appreciative and admiring of the work of the project director. And after five years they typically are in a situation where there is a significant portion of the teachers in the district using the new curriculum, another group of teachers who use it a little, and another group that does not use (and may not want to use) the new curriculum. If the grant is in, say, elementary science, then they feel that as a district they have in same way "handled" elementary science -- that it is an area they have paid attention to. And mind you, it is not always clear that the district wants a uniform program but rather they see the NSF funds as supporting a program that a portion of their schools and teachers may well want. But they do not want to impose that program on everyone, especially in an era of local control and site based management. The district may well want to be able to point to a range of approaches and a diversity of practices. So the NSF goal of uniform adoption and usage may well not be the district goal.

And district leaders look at this situation as the grant comes to an end, and they look at the tremendous resources they have had through the NSF grant, and they look now at the upcoming absence of those resources, and they see the cost of professional development, of the materials warehouse, and they also see all their other priorities and pressing issues. And they have to ask themselves not so much "How do we sustain this program?" but rather "Where do we go from here? What are our priorities and where does elementary science fit into the bigger scheme of things?" So the question of "sustainability" looks a little different from the point of view of those who have responsibility of running the whole district. In fact, they may well see the need to address OTHER areas, given how much money and attention has gone to the area already covered by the grant.

The term "sustainability" has within it a set of assumptions beliefs about the work of projects and about the reality of districts that, I think, are not always true. That is, there is an assumption that as a result of an LSC grant, and at the end of the LSC grant, a fully implemented program will be firmly in place that is, the whole house will be built and that now it will require less effort and fewer resources, but surely some resources and efforts, to "maintain" and "sustain" the program. These assumptions are, frankly, overoptimistic. But not because the grant was not successful . And not because the district does not value the work. Rather the problem raised by the issue of "sustainability" cuts much deeper.

Perhaps the implementation of a new curriculum is not really like building a house...Perhaps it is not a one time event, not even a five year event, but rather an effort that is more like keeping the Golden Gate Bridge painted. I was driving over the Golden Gate Bridge the other day and I was impressed by the crews that are always there working on the Bridge, and the equipment they have in place. These crews and their equipment are there full time. It is their only job and it is a full time job. The Bridge does not go out to get a grant to paint the Bridge. Rather the Bridge managers realize that keeping the Bridge painted requires steady ongoing work

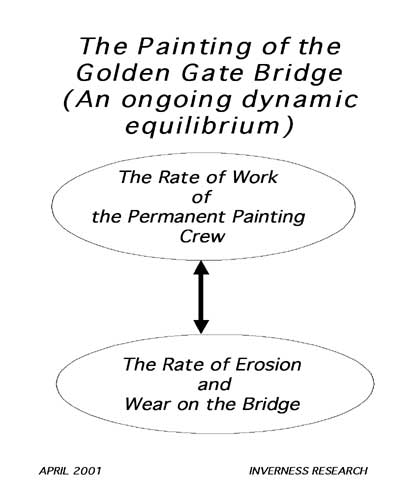

And I realized that the painting of the GG Bridge was a good example of a concept I used to teach in physics classes dynamic equilbrium. Dynamic equilibrium is when things are in balance in terms of what goes in and what goes out. A sponge that you want to keep wet is in dynamic equilibrium when the water that is evaporating is being replaced at the same rate by the water that is being added to the sponge (because there is someone there to continually wet the sponge). Similarly, the GG Bridge is in dynamic equilibrium because it is being painted at the same rate that paint is eroding away. There is always sun and wind and salt that works away at the paint job; it is not an exception or a surprise that the paint continues to erode away. Rather the Bridge managers have realized this fact and they realize it requires an ongoing steady effort, and the ongoing allocation of resources, to "sustain" the paint job.

Maybe in a similar way it would be better to think of curriculum implementation not as a one time event that leads to a "fully implemented program" but rather as a very good example of dynamic equilibrium. It is an ongoing effort, more like painting the Golden gate bridge. And using this idea we could say that a program is "sustained" when it is in dynamic equilibrium...

And there is a key thing to point out here. Districts that have implemented programs within them are like sponges that have water in them. Both suffer from rapid rates of evaporation. So many times we evaluators hear things like "our program was going well but"... "we have a high rate of teacher turnover... or administrative turnover... or financial crisis...or changes in state policy... or other priorities... " And all of these things cause program erosion, just as the wind and sun and salt work away on the paint job of the Golden Gate bridge, just as the sun and wind would cause the water to evaporate quickly from a sponge.

So in terms of dynamic equilibrium I do not think that there is much that NSF or anyone else can do to stop the processes of "program erosion." The key to achieving sustainability, when you think about it in terms of dynamic equilibrium, is to have some capacity for meeting those forces of erosion, for replacing the water that evaporates, for replacing the paint that is worn away. You cannot stop program erosion and program evaporation, so you need some way to continually put the program back in place, to constantly maintain it. This means that, in fact, you have to be constantly implementing the new curricula... So "sustainability" is thus achieved when you have program implementation at the same rate that you have program erosion and evaporation.

Now LSCs are great for getting the bridge initially painted or for adding water initially to the sponge. But they must be also be careful as they begin their work with systems that do NOT have much in place In fact, one has to be careful because the sponge can only absorb so much water and can only take it in at a certain rate. Pour the water too fast and the sponge simply drowns.

I was watching a recent episode of Survivor,. a rather dumb game show in the outback of Australia. The starving participants got the chance to "purchase" lots of rich food, a real treasure from their starving point of view. Only when they ate it all, they became very sick, because after a period of malnourishment, rich food, however good it looks, is simply indigestible. So the school systems have to be ready for the LSC nourishment we provide them. Just like starving people, it is better to nourish a weak system slowly over a long time time at a reasonable rate. And, again, the analogy to our grantmaking efforts, I think, is clear: You have to be careful how you add nourishment and capacity to a system that has little. If you go too fast, the system gets overloaded and it can actually be damaging to the long term health of the system. Go too slow and nothing of significance happens. Hence, the pace and rate of flow of reform is very important as one infuses energy and expertise into the system.

So what we need is not only to have an LSC initially and carefully wet the sponge or initially paint the bridge, but we also need to have the capacity within the system to continually maintain the paint, and to continually add water to the sponge(I am working hard to maintain my double metaphor here...).

And this need for ongoing replenishment, renewal, maintenance points out for me how very different education is than other enterprises. Especially it is different in terms of the way it thinks about and finances its own maintenance and improvement. The Golden Gate Bridge maintains and supports a permanent working capacity that is capable of continually "sustaining" and "re-implementing" the paint job. But, because resources are very very limited, education relies on short term grants, like the LSC, that must be then in turn be "leveraged" and "institutionalized." There is little real thought or design given to the process of sustaining the programs that are implemented.

Compare education to drug companies like Merck, or aircraft companies like Boeing, or software developers like Microsoft. They all spend a very significant portion of their revenues on improvement: on basic research, on developing the next generation of products, on refinements and upgrades, and on quality control and monitoring of their work... And most importantly, they do not ask the same people who produce the products to also have the full responsibility of improving the product or maintaining the product. The people who build current aircraft are not the same people who design the next generation. The people who run the company are not the same people who have responsibility for making the company Better. (Thus we have the old metaphor of trying to change the wheels on the car while we are driving it. Anyone who is serious about the wheels would have a different crew responsible for car maintanenace and time and resources would be built in for changing the wheels as well as the oil, etc.)

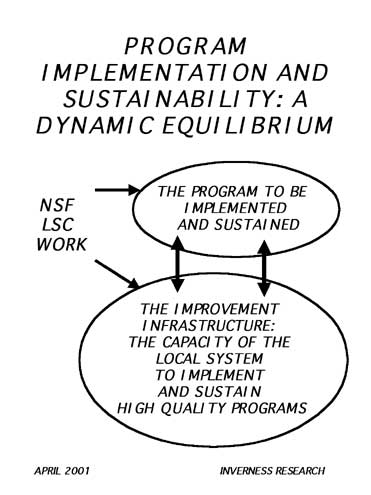

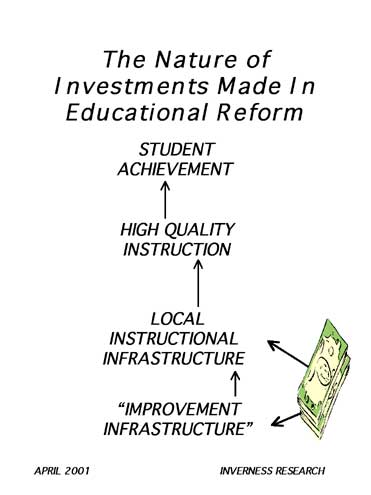

These companies have embedded within their structure what is called an "improvement infrastructure" They have resources and people and structures set up to monitor the quality of their work, to maintain it, and to improve it in the future. The people who work in the improvement infrastructure are not evaluated on the question of whether the company runs well. Rather, they are evaluated on the basis of the degree and nature of improvements and maintenance that they can bring about. The jobs of running the company, and improving it, are at least to some significant degre, separated from each other.

Typically, industry spends 8 to 15% of its funds on the improvement infrastructure. In education we as a nation spend less than 1% of all educational revenues on improvement. on all of the work we do that is specifically focus on IMPROVING education. Think about this: Math and Science Education is touted as a national priority; and NSF is certainly a lead player in the effort to improve math and science education. But their budget is on the order of .5 billion for all their K-12 education initiatives. This is .5 billion trying to improve a system that is 350 billion large. About one tenth of one percent. That is, out of every $100 to run education, we spend about 10 cents to improve math and science education. No wonder we worry about sustainabiilty! We are in some senses desperate because we by necessity really, really have to leverage our resources.

But equally important to the lack of resources is the lack of conceptualization. States, districts and schools do not have any way to to think about their own ongoing improvements. There are fewer and fewer district specialists in science and math; and there are fewer and fewer state or regional specialists. And these people often have many duties (eg science fairs) that are really about running the system -- and not improving the system. So in education I think that we do not even think about having people, institutions and structures that are truly part of an ongoing improvement infrastructure for education. There are universities, and labs, and even district science and math specialists, but most of these people and institutions live on "soft money." They are a shifting and transitory improvement infrastructure.

The hope is that people on soft money with lots of expertise and with sufficient resources can create curriculum, can help design professional development, and can "CATALYZE" change in our states, districts and schools. And there is no doubt that they do very well with the funds they have . But the whole structure is temporary, and states and districts do not have the ongoing normal assumption that they will have money, people and structures all devoted to ongoing program maintenance and improvement . Unlike the Golden Gate Bridge they do not have permanent maintenance and painting crew. Rather, they hope that those who already overloaded in running the system can also find the time, energy and expertise to improve, maintain, and monitor the system.

Think of how this might be different. What if there were a law that said all states and districts had to devote 10% of all funds to an "improvement infrastructure" ? They had to devote resources so that they had people who had the time, expertise, resources and mandate to improve the system. Surely it is clear that districts who DO somehow accomplish a lot with their NSF and other grants have people who are, at least for a short time, are working effectively as an improvement infrastructure. But districts and schools are strapped right now, and they devote any additional resources to immediate needs and crises, not to investing in a long term infrastructure for improving their work. (This is very clear in the degree to which both states and districts have eliminated science and math specialists over the past few years.)

So, back to our Bridge and Sponge metaphor. What I am saying is that 1) the forces of erosion and evaporation are inevitable; and 2) there needs to be an ongoing permanent capacity built into the system for putting back into the system what is lost that is, an infrastructure needs to exist and be exclusively devoted to maintaining and improving program quality. But there is not such a system or, unfortunately, even the conceptualization of such a system.

And there is another paradox or irony here. The more innovative a curriculum is, and the more it is different from a traditional curriculum, the more that it needs ongoing support and maintenance. So when a district chooses to implement an NSF-funded curriculum that is focused on inquiry, engages students in long term projects, is rigorous in its content, uses technology in authentic ways, and/or teachers math and science content in "contextualized settings," then the amount of support that is needed will be much greater, because the rate of evaporation and erosion will be much greater. So the better the program that NSF funds pay to implement, the higher the erosion forces, and the greater the need for ongoing efforts to maintain the program.

And similarly we should note also that when NSF funds LSCs in the "most needy" districts, it is like putting a sponge in the desert: the rates of evaporation will be very high. Or it is like having a bridge in an environment where the forces of erosion are very high.

So if the goal is to "sustain" an innovative curriculum in a highly needy district, then there needs to be a very strong ongoing source of support, a strong improvement infrastructure but this, of course, is exactly what is likely to be lacking in such districts.

I want to say it again, because I think that there is a horrible fact to be confronted here. The more that NSF seeks to serve the most needy students in the most needy districts, and the more it seeks to implement very high quality programs, the greater the forces of erosion and program deterioration (turnover, instability, changing leadership, shifting priorities, lower quality teachers, etc.). And all of this means that much, much greater levels of ongoing support will be needed and that is exactly what is almost completely absent in urban and rural settings that are very poor.

Now does this mean that NSF should stop trying to assist the most needy districts, or give up on high quality programs???? No, not at all but it might mean that we should be more realistic about how much change can be brought about and also sustained. Maybe it would be better to be less ambitious in the degree and nature of change, and more ambitious in trying to develop ongoing capacities within the district for program maintenance and support.

Another way of saying all of this is that one has to be careful about the match-up of soft money and hard money. Soft money can provide a district with all the resources and work of an LSC; but if the district lacks the hard money to provide itself with an improvement infrastructure, an ongoing set of supports, then there is a great likelihood that the LSC work will, in fact, not be sustained...

What gets sustained in a district is what can get supported. The sponge will stay as wet as the supply of water that is available to refresh it., not as wet as it gets when we pour a bucket of water on it. The bridge will stay as painted as there are permanent painters and paint to work on it, not as painted as it gets under best conditions. This is why textbooks are, in fact, "sustained" in most districts. The permanent infrastructure, and district capacity, is just sufficient to adopt, buy and distribute texts, but not sufficient to provide all the supports needed for, say, an inquiry-based kits program.

This is why the question of "sustainability" for me begs a deeper question: How can we begin to help education leaders and the public see the need for ongoing permanent improvement infrastructures for their state and local systems? When we raise the whole challenge and problem of "sustainability", we are in essence saying that the work of the soft money has gotten out in front of the work of the district's operating money. We somehow need to better connect the soft money and the hard money.

Somehow we need to use the NSF grants and other soft money not to do the work of reform but rather to help augment the permanent capacity of districts to both improve and maintain their programs. NSF could help states and districts put in place more permanent improvement infrastructures. The programs that districts and schools end up with are the ones that they themselves can support and can understand. Thus, while it is important to have efforts like the LSCs bring in resources, energy and expertise, we also desperately need to change the structure and funding of districts and schools so that it is normal, and not abnormal, to find highly qualified people working full time on a permanent basis to ensure that the quality is always being checked and improved.

And, very importantly, I think it is critical that we need to find ways to evaluate the investments made by NSF on this basis. That is, LSCs and other NSF programs should be evaluated as to how well they build the capacity of districts to implement, maintain and improve their science and math programs. And, frankly, trying to evaluate them in terms of student achievement is conceptually wrong and a fatally flawed endeavor. It sends all the wrong messages, wastes time and energy, and is ultimately very counterproductive. Trying to find (and jury-rig) evidence of student achievement may well be detrimental to achieving the sustainability of our efforts (in spite of the fact that the political thinking is that student achievement is key to sustainability but this is a longer discussion). I think we would all be better off to simply have the courage and wisdom to invest in the long term growth of capacity of districts and states and to make the case for our investments on that basis. We need to design and evaluate our investments so that they help to build the improvement infrastructure within states, regions and districts. Otherwise we will continually be asking ourselves, "How do we 'sustain' the (unsustainable) programs we have tried to put in place?"

P.S. Updating the old fish proverb

"Give a man a fish and he will eat today; Teach a man to fish and he will eat everyday"

New version: For years the funder gave fish to the people in the community every year. But every year when they returned, the people had no fish of their own. So they decided to fund a professional development program to teach people how to fish. And this worked well, at least on the surface. People came to the workshops and learned how to fish. Some even said it was a life changing experience that they really came to believe in fishing.

But still when the funders came back the next year no one was fishing. They were perplexed by this. So they asked: we had good professional development; why is no using what they learned. So the people said: Yes, we learned how to fish; we even came to believe in the value of fishing.. But we have no tackle, no boats. We have no money to buy the bait. We lack all the critical supports needed for fishing.

So the Funder realized they needed a more systemic approach they had to make sure that the supports were there. So they funded the purchase of boats, of tackle, and of bait. When they left there was a small group of ardent fishing advocates well trained and well prepared to go fishing.

But when they returned three years later, there were no fish. And there was no one fishing. And the people explained: Well, for a while it was great. We had what we needed and we fished everyday. But over time it kind of fell apart. Some of the key people, our best veteran fisherman, retired. And there was no people or time or money to train others how to fish. There are still a few wily old veterans who go out and fish on their own, but they are kind of mavericks and purists. And there was no money in the community to keep up the boats. And we could not get money for a warehouse to store the tackle and bait. And we fished out the easy grounds and it was much harder to fish farther afield. And the species of fish changed so that we werent as good catching them.

And the rewards and incentives were simply not there it takes a lot of work and effort to fish! And while it is a noble endeavor, we just could not get enough people committed enough to keep the whole thing going.

And if that were not enough, we dont think people in the community ever really got to like fish very much. For years they had been eating cheeseburgers, and they liked and trusted cheeseburgers. And they did not trust fish, even though there is lots of scientific evidence that fish is better for them. So in truth the community never really bought into the whole fishing thing.

The five year fishing program we had was great, no complaints there But we just couldnt sustain it

Mark St. John

Inverness Research Associates

Box 303

Inverness, CA 94937

415 669 7156

415 669 7186 fax